UNCTAD’s Least Developed Countries Report 2023 calls on the global community to urgently address the critical financial challenges faced by the world’s 46 most vulnerable nations.

» See the map and list of LDCs

Multiple global crises, the climate emergency, growing debt burdens, dependence on commodities and declining foreign investments into LDCs have strained their finances, jeopardizing their progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including a low-carbon transition.

The upcoming Loss and Damage Fund, set to debut at the 28th UN climate change conference (COP28), could be a game changer if LDCs are among the main beneficiaries, enough resources are available, and disbursements are swift.

But their financing requirements go far beyond climate concerns, encompassing broader economic and social challenges. The report calls for a lasting, multilateral solution to the debt crisis in these countries and for the mobilization of both the development and climate finance they require.

It also underlines the pivotal role domestic agents can play, particularly central banks, in enhancing the mobilization of national resources and steering financial flows towards a green structural transformation in these countries.

Plugging funding gaps

and expanding fiscal space in LDCs

LDCs’ shrinking fiscal space limits their ability to implement development policies and forces tough choices, such as choosing between paying their external debt or investing in health, education and climate action.

Fiscal space is essentially a government's capacity to absorb drops in public revenue. Its decline in LDCs is evident in key indicators, such as their debt-to-GDP ratio, which grew from 48.5% in 2019 to 55.4% in 2022 (the highest since 2005). See more in the section on debt.

Their fiscal space has been squeezed by global crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, the climate emergency and the war in Ukraine, which triggered food and energy price hikes worldwide.

To cushion the blow, LDCs have borrowed and spent more to strengthen social safety nets and economic support, as at least 15 million more people in LDCs have fallen into extreme poverty since the pandemic.

Their dependence on volatile commodities, such as oil, copper and cotton, contributes to the problem. Between 2019 and 2021, a staggering 74% of LDCs relied on these raw materials for at least 60% of their merchandise export earnings. When prices drop, their fiscal space shrinks drastically.

Urgent, bold action from the international community is critical to ensure LDCs have better access to affordable, long-term international financing, especially from public sources.

While external financial support is important, LDCs must also enhance domestic resource mobilization. For example, their median tax-to-GDP ratio stood at 11.6% in 2020, compared with 16.3% in other developing countries and 23.2% in developed countries.

UNCTAD calls on

-

1Donor countries to urgently raise their official development assistance to meet internationally agreed targets, which would have generated an extra $35 billion to $63 billion in 2021 alone.

-

2Multilateral development banks to urgently raise funds in international capital markets to make hundreds of billions of dollars available to LDCs that’s concessional, low-cost and long-term.

-

3Development partners to help LDCs strengthen their state capacity to raise taxes, manage fiscal resources and execute long-term spending on development projects and climate adaptation.

-

4The international community to improve cooperation to strengthen tax norms, combat illicit financial flows and facilitate revenue collection in LDCs.

Making the global financial system

work for LDCs

The international financial architecture lacks appropriate, tailored and targeted financial mechanisms for LDCs, and post-COVID-19 reforms have fallen short of expectations.

Promises and commitments on international climate finance and official development assistance (ODA) have gone unfulfilled. The external financing that LDCs can access is expensive, insufficient and comes with economic and political strings.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, LDCs' needs for external finance were already high. UNCTAD estimates show that pre-pandemic they needed over $1 trillion each year to double their share of manufacturing in GDP – an amount more than triple their fixed investments in 2021.

Amid ongoing global crises, their needs have ballooned. UNCTAD calculations show that, relative to countries’ economies, LDCs bear the highest per capita cost to achieve the SDGs. Explore the analysis of SDG costs.

The report highlights LDCs’ limited influence on development finance decisions that affect them, regardless of whether the international sources are bilateral or multilateral, public or private.

For instance, LDCs represent only 4% of the World Bank's voting rights and in 2021 received less than 2.5% of the International Monetary Fund’s special drawing rights issued in 2021.

The report stresses that effective climate and development finance for LDCs must address three key dimensions: amount, appropriateness and access.

Funds must be available at the required scale, delivered through low-cost instruments and underpinned by international financial mechanisms adapted to LDCs’ specific needs.

Otherwise, these countries will be unable to reach the SDGs.

UNCTAD calls on

-

1Bilateral donors to meet their commitments by increasing official development assistance (ODA) to levels targeted in international agreements.

-

2Donor countries to substantially increase grants to LDCs, with simplified access modalities and lower transaction costs.

-

3Developed countries to commit to rechannelling $100 billion in Special Drawing Rights in the near future to help LDCs get back on track to meeting their sustainable development goals.

Finding lasting solutions

to the debt crisis in LDCs

As of April 2023, six LDCs were in debt distress and another 17 were at high risk of debt distress. Explore UNCTAD’s debt dashboard.

Most LDCs’ debt problems are structural, due to their persistent current account deficits and dependence on volatile commodity exports. Sudden price drops can drastically cut government revenue, making external debt repayments more challenging.

Almost all debt sustainability indicators have deteriorated for LDCs. Their total external debt hit $570 billion in 2022, with the public and publicly guaranteed portion reaching $353 billion – more than three times higher than in 2006.

As a result, they’re spending five times more on debt interest payments than a decade ago. Even worse, since 2018 LDCs as a group have spent more on debt than on education – with 11 of them spending more on repayments than on education and health combined.

LDCs' shift towards private lenders, combined with a diverse mix of short and long-term obligations to creditors of different risk levels, has added complexity to their debt profiles.

Finding immediate relief and lasting solutions to the growing debt burdens in LDCs is essential for them to rebuild the fiscal space necessary to invest in sustainable development.

This requires grants, concessional loans and, ultimately, a multilateral debt workout mechanism that is transparent and responsive to LDCs’ needs.

The debt workout mechanism is paramount, given that a large portion of LDC debt isn’t covered by the G20's Common Framework for Debt Treatment.

UNCTAD calls on

-

1The International Development Association to grant all LDCs access to loans to help balance their long-term and short-term debt and categories of creditors.

-

2Official creditors to offer LDCs in debt distress emergency lending on concessional, affordable terms and to convert maturing short-term loans into long-term ones.

-

3Multilateral development banks and creditors, especially the Paris Club, to enhance coordination and establish a flexible and transparent debt workout mechanism, including a payment standstill when a debtor country starts negotiations.

-

4Development partners to provide debt relief in addition to development finance, including official development assistance.

Tailoring climate finance

to LDCs’ needs

The report calls for more climate-specific finance for LDCs, which suffer the most from climate change but contribute the least to its causes.

As of 2021, 17 of the 20 most climate-vulnerable and least climate-prepared countries were LDCs, which have suffered 69% of global climate-related deaths over the last 50 years.

LDCs’ share of global climate finance flows doesn’t reflect their oversized vulnerabilities. Between 2016 and 2020, they received about $12.6 billion per year – an amount proportional to their share of developing countries’ total population.

Only 45% of the funds targeted climate adaptation – a key priority for LDCs. More focused on mitigation, such as reducing greenhouse gases, even though they contribute just 4% of global emissions.

Worryingly, a third of the finance was in loans rather than grants, raising the risk of climate debt traps.

The report highlights the need for not only more climate finance but also a bigger share of grants and a stronger focus on adaptation. LDCs, along with small island developing states, should be given priority in new climate financing mechanisms, such as the upcoming Loss and Damage Fund.

The report outlines conditions to maximize the fund’s impact, such as addressing both the immediate costs of extreme weather events and longer-term, accumulated climate damage, and avoiding additional costs like insurance premiums.

Because most climate finance comes from non-climate-specific mechanisms, the report stresses the need to set climate-specific targets in addition to those for official development assistance and to keep climate and development funding separate in accounting.

UNCTAD calls for

-

1LDCs to be among the main beneficiaries of the Loss and Damage Fund due to their heightened vulnerabilities to climate change.

-

2The forthcoming Loss and Damage Fund to consist mainly of grants and financing sources that have low transaction costs with rapid disbursements.

-

3A global unified accounting framework for climate finance to enhance transparency and prevent the double counting of development finance and climate finance.

-

4LDC-specific targets for climate finance by donor countries, with an emphasis on adaptation, in addition to the current targets for ODA.

Central banks can play

a pivotal role in climate action

Given the financial challenges posed by climate change – the damages and need for adaptation and mitigation – it’s crucial for central banks to integrate climate factors into their monetary policies.

Such measures are commonly referred to as “climate” central banking.

But given the need for policy coherence to avoid severe tradeoffs in climate central banking, the report recommends caution. It underlines that governments, not central banks, should address these tradeoffs.

If guided by industrial policy goals that target a green transition, these banks can play a pivotal role in managing climate-related risks to the financial system and economy and can channel funds towards a green structural transformation.

When a central bank channels more finance to decarbonization projects it helps make domestic industries less vulnerable to climate policies implemented in other countries, improving the resilience of the country’s economy and financial system.

To champion climate-centric development, LDC governments should consider updating central bank mandates. However, having a climate mandate doesn’t guarantee the effective use of climate central banking tools.

The report stresses that these tools should align with other economic and social policies to avoid undermining other developmental goals.

Central banks should also ensure the tools fit the local economic structure. For example, in an economy in which formal credit constitutes only a small proportion of the total credit given to households and firms, the introduction of climate central banking would have a limited impact.

The report provides a decision tree for decisions on when to use climate central banking and which tools to employ.

Framework for LDC central bank mandates and climate tools

-

1If the central bank has a mandate to support sustainable development, it should use climate adaptation and mitigation tools.

-

2If the bank has a broad mandate – for example, including price or exchange rate stability, growth or employment – it should develop climate-adjusted analytical frameworks.

-

3If it’s responsible for financial stability and uses a strong macroprudential approach, it should also use climate risk exposure tools.

-

4Before using a climate tool, the central bank should ensure it aligns with the structure of the local economy and other social and economic policies.

LDC facts and figures

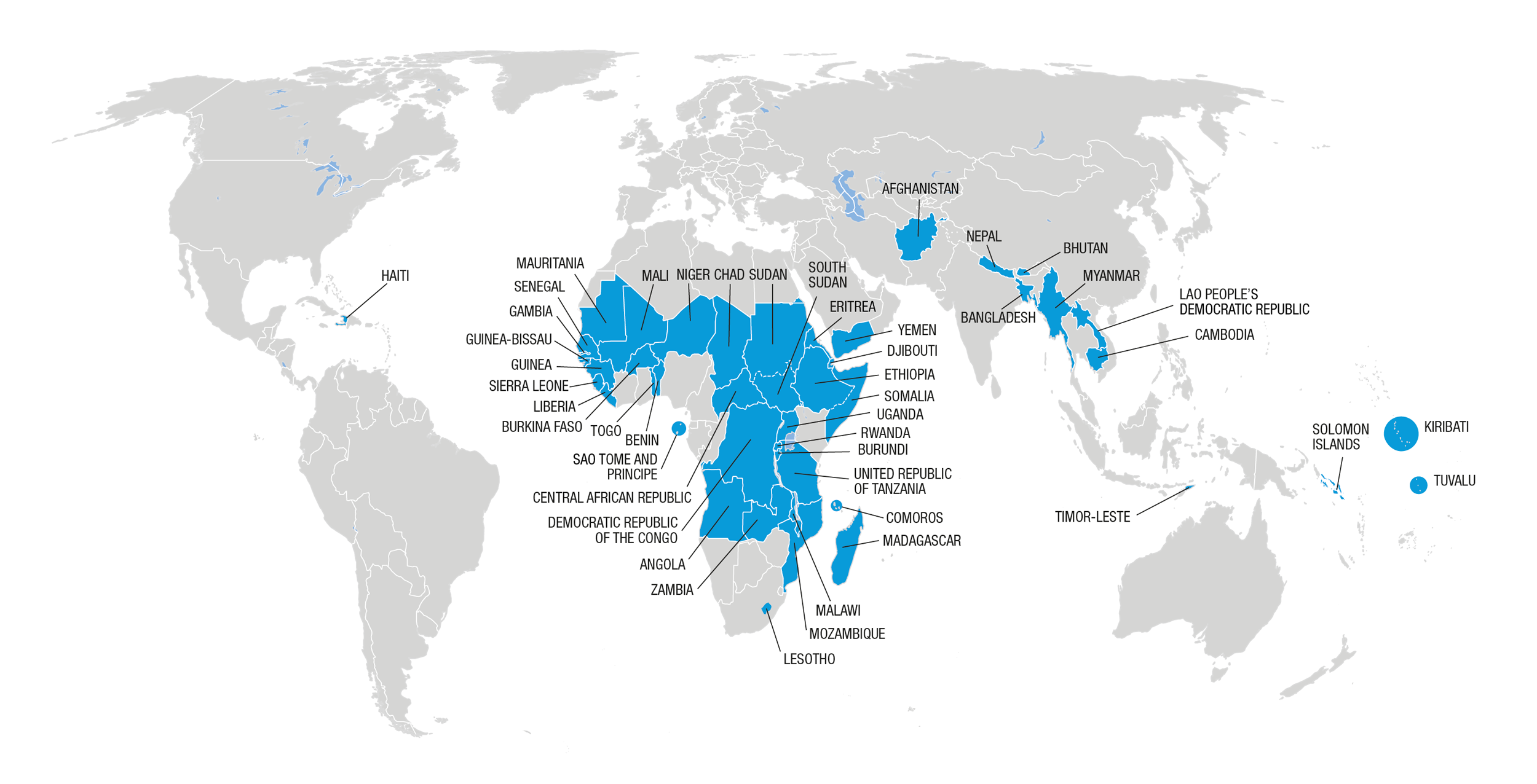

Where are LDCs located?

The UN established the LDC category 51 years ago. The list of LDCs has expanded from an initial 25 countries in 1971, peaking at 52 in 1991, and stands at 46 today, with only six countries having graduated – stopped being an LDC – to date.

They are distributed among the following regions:

- Africa (33): Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Togo, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania and Zambia.

- Asia (9): Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar, Nepal, Timor-Leste and Yemen.

- Caribbean (1): Haiti.

- Pacific (3): Kiribati, Solomon Islands and Tuvalu.

See UNCTAD's page about the least developed countries for the latest information.

How do countries ‘graduate’ from least developed country status?

The list of LDCs is reviewed every three years by the Committee for Development Policy (CDP), a group of independent experts who report to the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). Following a triennial review of the list, the CDP may recommend to ECOSOC, countries for addition to the list or graduation from LDC status. The next triennial review is scheduled to take place in March 2024.

To graduate from the LDC category, a country must meet the established graduation thresholds of at least two of the three criteria for two consecutive triennial reviews: namely: (i) income per capita, (ii) an index of human assets, and (iii) an index of economic and environmental vulnerability.

Countries that are highly vulnerable, or have very low human assets, are eligible for graduation only if they meet the other two criteria by a sufficiently high margin. As an exception, a country whose per capita income is sustainably above the “income-only” graduation threshold, set at three times the graduation threshold ($3,918 for the 2024 triennial review), becomes eligible for graduation, even if it fails to meet the other two criteria.

The six countries that have graduated from least developed country status since the creation of the category are:

- Botswana in December 1994

- Cabo Verde in December 2007

- Maldives in January 2011

- Samoa in January 2014

- Equatorial Guinea in June 2017

- Vanuatu in December 2020